In researching the Hospital Creek Massacre just north of Brewarrina in 1859, I kept coming across the likes of Keith Windschuttle refusing to accept that it even occurred. He writes; “I looked up Trove to see if any of the country or metropolitan newspapers of the day had reported the incident, but found no mention of it”. That’s Windschuttle for you, if it did occur it was merely an “incident”. He continues: “I couldn’t find anything about it in New South Wales parliamentary records in 1859, or any year thereabouts either. This was surprising since the killing of 400 Aborigines, or anything like that number, would have amounted to the worst single case of indigenous slaughter in the history of Australia, or indeed in the history of any British colony to that time.”

Cornelius Bride, Pilliga Jemmy and Thomas Gordon Dangar and The Hospital Creek Massacre

There are some who still deny that a massacred occurred at Hospital Creek in 1859. This paper shares and examines the writings and voices of contemporary indigenous and settler peoples confirming that hundreds were massacred at Hospital Creek and thousands died in the few years before and after 1859.

In her book, ‘The Memory Code’, Lynne Kelly explains how ancient cultures used memory techniques to store and transmit vast amounts of information across generations, potentially for many thousands of years. In the case of Ngunnhu (The Brewarrina Fish Traps), given that they have physically been there for some 40,000 years, it is highly likely that the origin or ‘dreaming’ story is that old and has been passed down from generation to generation.[1]

Baiame the creator god and sky father created Ngemba, Murrawarri, Euahlayi, Weilwan, Ualari and Barranbinya country, the land and all living things. He created rivers, creeks, lakes and waterholes and lined them with towering red river gums, black box and lignum. He populated them with golden perch (yellowbelly), Murray cod, yabbies, and freshwater mussels.

He created flood plains and plains of saltbushes and grasses and sandhills with white cypress pines. He created over 200,000 pairs of straw-necked ibis, multitudes of pelican and black-fronted dotterel, bittern, pied, little black and great cormorant, freckled and pink-eared duck, black swan, glossy ibis, whiskered tern, royal spoonbills and darter.[2]

He created emu, wedge-tailed eagle, and various parrot and cockatoo, kookaburra, dove, willie wagtail, and sacred kingfisher, red-tailed black cockatoo, and barking owl. He created innumerable species of lizard, snake, kangaroo, frog, goanna and possum, insect, and men and women.

Baiame taught the people the lore of country and came to visit Ngemba country at a time of a drought. He brought his two sons, Booma-ooma-nowi and Ghindi-inda-mui to help him build the fish trap weirs, and instructed each of the families on how to maintain their specific weirs and share with other clans.

While ‘country’ was arid, it supported thousands of people, and it was common for 4,000 or more people to gather at the fish traps every spring. There they would hold corrobboree, to share the fish, hold initiation ceremonies, perform storytelling, dance and singing to share cultural knowledge and values, including kinship structures, strengthen social bonds, connect with the spiritual realm, and have meetings to trade and give gifts.

The relationship between all living things on ‘Country,’ is symbiotic, and until the 1840s, ‘Country’ was healthy.

In 1828, Captain Charles Sturt and Hamilton Hume explored the Wambuul, the Macquarie River which led to the Bogan which he named the Bogan River before reaching the Baaka and naming it the Darling River in 1829.

Sturt described the large community camps and noted there were permanent pathways following the rivers and leading to camps. He observed that ‘The paths of the natives on either side [of the river] were like well-trodden roads.’ Despite most groups appearing to be highly mobile bands, Sturt encountered signs of village-like communities on several occasions. For example, following the Macquarie River, he found a group of 70 huts, each large enough to hold 12-15 men. They all had the ‘same compass orientation’, and one particular hut was found to contain two large nets, about 90 yards in length.[3]

On two occasions during his 1831–32 expedition, Major Sir Thomas Mitchell noted weirs through the Upper Darling catchment. On the Gwydir River, he (Mitchell 1839, p. 100) observed trellises constructed from interwoven twigs and erected across the various ‘currents’ in the river. These Barwon River, ‘several wears [sic] for catching fish, worked very neatly, stood on ground quite dry and hard’ (Mitchell 1839, p. 93).[4]

In the early 1840s, settlers, including William and Nelson Lawson, Henry Cox, and George Joseph Druitt, established pastoral runs in the area. The Lawson brothers established holdings called Walcha and Mohanna, while Cox established Quantambone, and Druitt established Brewareena West. Walcha became known as Walcha Hut and then Brewarrina; from the Weilwan word ‘burru waranha’, which translates to “Acacia clumps” or ‘place where wild gooseberry grows’.[5]

These early squatters had been progressing westward along the Barwon River and there were few who sympathised with the indigenous people being removed from country. One ‘Voice From The Bush’ wrote:

GENTLEMEN. On looking over your paper of the 9th instant, my attention was attracted by some remarks of yours relative to ” outrages committed by the blacks on the Barwin [sic],” which, as is usual, pictured the unfortunate aborigines of this country in very unfavourable colours.

It is to be regretted that the blacks do some-times commit depredations on life and property, but that they should always be in the wrong, and be the aggressors in every bloody conflict that occurs between them and the whites, is not at all probable. If they could but communicate through the press, or otherwise, their grievances, if they could bring to light the numerous wrongs to which they are frequently subjected by the whites, then surely the persecuting spirit ever evinced by the press, as well as by a large portion of the public, towards them, would be measurably appeased.

As a people, we have doubtless been very remiss in our duty towards the aborigines, for we have taken possession of their hunting grounds without conferring upon them the boon of civilization. Neither can we close our eyes to the fact that in all the older settled districts the blacks, from the introduction of intoxicating drinks, and of a disease to which they were happily strangers prior to our intercourse with them-to which I may also add the application of the musket-have become almost extinct ; a circumstance disgraceful to us as a Christian and enlightened people, and which will ever remain an indelible stain on our fair fame, and will be transmitted to posterity on the page of history !

Perhaps for the welfare of society, it is necessary that the aborigines should in most instances be amenable to our laws; but when they commit a breach thereof, is it just and reasonable that we should inflict upon them the same measure of punishment as is awarded for similar offences to those amongst ourselves who, being enlightened and instructed, do not, like the benighted aboriginal savage, sin without knowledge ?

In censuring the government, and in exclaiming against the blacks, much pains has been taken. But, gentlemen, permit me courteously to suggest whether or not the time so occupied might not have been more honourably and advantageously employed in co-operating with the former in the difficult task of devising plans for the civilization and improvement of the latter.[6]

In 1845 when these early squatters were occupying Ngemba, Barranbinya and Ualarai country, Cornelious ‘Con’ Bride had disappeared from his home at Portland Bend on the Hawkesbury River. The son of emancipated Irish convicts Ellen and Bartholomew Bride, Con was ten years old in February 1845 when his mother placed an advertisement in the Hawkesbury Courier and Agricultural and General Advertiser. He had been missing for nine days after leaving home to assist a General Dealer traveling to Sydney.[7]

Between his birth in 1835 and when he went missing in 1845, there were at least 89 acknowledged massacres of indigenous peoples across the colony. It is estimated that as many as 1,238 people were killed in massacres that included the Myall Creek massacre in 1838. That massacre killed 28 people and there were another 17 massacres where more than that number were killed and 4 of them were of 100 people or more.[8]

Also in 1845, Thomas Gordon Dangar, stepson of Thomas Dangar was 17 years old and attending Sydney College.[9] His two step-uncles Henry and William had acquired over 300,000 acres of grazing land that included Gostwyck, Paradise Creek, Bald Hills, Moonbi, Buleori, Karee and Myall Creek.

When Thomas completed his studies,

he commenced life before the mast upon a New England squattage, and afterwards on the Condamine. In 1849 he changed his course to the Namoi, living upon his uncle’s station properties, Cubberoo, Drildool, and other runs, and, eventually, starting upon his own hands, became a large squatter, making his headquarters at Bullerawa, upon the Namoi River.[10]

He was just 28 years old in 1857 when he purchased Bullerawa from his step-uncles. He had been managing the property since 1849.

Over the next decade he established or acquired Tinnenburra horse station on the Warrego and cattle runs such as Bunnowana, on the Darling River; Walcoo, on the Bogan River; Gingi, on the Barwin River; Pilliga, Milchomi, Tallaba, and Cutabri on the Namoi River; Oreel, on the Thalafa River; Belah, on the Castlereagh River and the Grawin and Wilby Wilby, on the Narren River. He built the largest stockyards in Australia at Gingi,

covering six and half acres, which could handle 10,000 head of cattle. Stock from the stations in the area, which lay within the Liverpool Plains and Bligh Squatting Districts, were driven to market up the Namoi and across the Liverpool Range to the Hunter valley, sometimes stopping at the boiling down works at Tamworth.[11]

By the mid-1850s, Bride, and his brother Batholomew jnr. had established Belar Homestead at Coonabarabran, where Con later registered a horse ‘brand’, the letter a, and Batholomew registered the number 3 with a semicircle below it. It is possible that they supplied horses to Thomas Dangar and that Con had already taken on an aboriginal “stockman”, Pilliga Jemmy.

Responsible government in the form of a Legislative Council was only introduced in 1855. In the preceding years, few new squatters had attempted to seize the grazing country on the Barwon and upper Darling River flood plains. This country had been

abandoned on the breaking up of the ’39-40 droughts. Sometime later the blacks killed two or three men (Suttors, I think) at ‘The Murdering Stumps,’ on the Bogan, and the Crown withdrew the whole country lying between there and Mount Murchison (now Wilcannia), and also between this latter and the Fishery (Brewarrina), from lease, and it was not till ’57 that the country was again thrown open.[12]

Dangar employed Bride and between 1857 and 1859, Bride, Pilliga Jemmy and ten stockmen drove a herd of ‘2000 heifers to reoccupy Bunnawana and Warrawene’[13] They followed the Namoi and Barwon rivers to the fish traps, and occupied Bunnawanna station on Barranbinja country. They based themselves at Quantambone and were grazing their cattle on Ualarai country to the northeast of the small settlement that would be gazetted as the town of Brewarrina in 1861.

At this time, the newspapers were reporting on the Indian Rebellion in which some 6,000 British and 800,000 Indians were killed or died of starvation. Newspapers throughout the length and breadth of the colonies reprinted an article containing the following paragraph:

We imagine that our right — the right of the British government and people to the possession and civilization of this country — is equally well founded with the similar right of occupancy and supremacy in India. Consequently, the violation and murder of women and children by the aboriginal inhabitants ought to be as much a matter of abhorrence, and as just a cause for retribution in one country as in the other.[14]

Dangar and Bride, who were two young men setting out to establish vast squatting runs in the northwest of the New South Wales colony may have shared this belief. G. M. Smith claims that when he met Bride around 1883, he told him that

That affair got me a bad name down below with the people who never had to deal with the natives in their wild state. Had they been in my place probably they would have spilt more blood than I did… the Government was well aware of the fact that the work we were doing outback could not be done with white-gloves on, and, therefore, were not too ready to take action in such cases, but depended on the humanity of the white settlers to spare the natives as much as possible.[15]

Bride was referring to the massacre at Hospital Creek in 1859.

In the 1860’s however, there were only rumours that a massacre had taken place. Unlike the Hornet Bank massacres between 1857 and 1859, in which hundreds of Yiman were massacred in response to the massacre of 11 settlers on the Dawson River in central Queensland, there was no official report on the Hospital Creek massacre and nothing in any newspaper until 1869 when a first-hand account was published in the Dubbo Despatch by Thomas Manning. G.M. Smith’s recollections of a conversation with Bride were published in 1928 and William Emanuel Kerrigan, son of William and Eliza Kerrigan who was the first ‘white child’ to be born in the area in 1865, wrote about the massacre in his journal. His father and uncle Robert Kerrigan both knew and worked with Bride.

It is highly unlikely that Thomas Dangar was unaware of the massacre on his Quantambone run. While he had only been 9 years old in 1838, when stockmen on his step-uncle Henry Dangar’s run at Myall Creek massacred 28 men, women and children, he must have been conscious of the potential repercussions. Seven cattlemen had been convicted of murder and executed for the Myall Creek massacre when the Attorney General of New South Wales, John Plunket prosecuted two trials to convict them.

The most common response by the newspapers to the death sentences was one of widespread sympathy for the accused and there was significant opposition to the verdict among settler communities. While some publications upheld the principle of equal justice under the law, the prevailing tone of the press reflected deep anxiety about the implications of the verdict for frontier society.

Twenty-one years later, the press coverage of massacres was selective. Many incidents of violence against Aboriginal people went unreported or were relegated to brief, vague mentions. The lack of detailed coverage was not accidental; it reflected both the priorities of editors and the expectations of their readerships. When massacres were mentioned, coverage tended to be cursory, with minimal investigation or follow-up.

Massacres in other countries, however, were widely reported. In an article reprinted in at least nine newspapers across the colony in 1859-60, was the account of a massacre remarkably similar to the one at Hospital Creek.

‘Never as journalists, have we been called upon to comment upon so flagrant and inexcusable an act of brutality, as is involved in General Kibbe’s last Indian war — a scheme of murder conceived in speculation and executed in most inhuman and cowardly atrocity. If the account of Mr George Lount, a resident of Pitt River, be true General Kibbe and all the cowardly band of cutthroats who accompanied him should be hung by the law for murder; for murder it is, most foul and inexcusable. Sixty defenceless Indian women and children killed in their own rancherias at night, by an armed band of white ruffians. The massacre of Glencoe does not afford its parallel for atrocity. This band of Indians were friendly, had committed no outrages, were in their own homes, on their own lands, only 10 Indian men with them, unarmed and helpless. General Kibbe’s name, if responsible for these acts, should be more infamous than Haynau or any of the licensed butchers of tyranny. This massacre is not excused even by the common plea of expediency, policy, or necessity, which has palliated the butcheries of history. The Indians have been driven from their hunting ground by the white man’s stock. Their fishing racks have been destroyed by the caprice or for the convenience of the white man. Their grasshoppers are driven away by the cultivation of the soil. Their acorns are exhausted by the white main’s hog and driven to desperation by actual want and starvation they have stolen the white man’s ox. When Governor Wellar, on the 15th of September, authorised W J Jarboe to organize a company of 20 men to make war on the Indians who had been stealing stock, every man provided his own horse, rifle, revolver, knife, and ammunition. In 70 days, they had 15 battles with the Indians; killed more than 400 of them.[16]

This was just one of many reports of massacres in California where more than 1,500 men women and children were killed in at least 5 massacres between 1857 and 1859.[17]

Across the world, the killing of indigenous people was an everyday event, and the description of the Glencoe massacre could have been used to describe the Hospital Creek massacre. Similar causes and outcome.

As though the killing of aboriginals was a common event, Con Bride moved on. Either under instructions from Thomas Dangar or striking out on his own, by late in 1859 he had set off up the Warriku ‘the river of sand’ with Pilliga Jemmy.

In a newspaper article about the Bushranging days in New South Wales, it was claimed that Bob Kerrigan had accompanied Bride in driving Dangar’s cattle to Brewarrina and then on his exploration of the Warrego River.[18] It is more likely that Kerrigan and others from Brewarrina moved to Kula country several years later. Bride

… may also be regarded as the sole pioneer settler of the now famous Warrego River, having been the first man who penetrated the (then unknown) country between the Upper Darling and the Warrego, some ten years since which he did accompanied by the faithful ‘Pilliga Jimmy,’(sic) the truest darkie that ever breathed.[19]

It is almost certain that Bride explored the Warrego as far as Cunnamulla, some 360 km from the Darling, because Dangar established a run just to the north of there. Bride returned to Bunnawanah,

which he reached by a shorter route, thoroughly exhausted and wearied out for want of sleep-neither he nor Jimmy having had more than a few hours’ sleep alternately, while one guarded the other, revolver in hand, for fear of an ambushed enemy. Con shortly after this, with a commendable unselfishness, made public his discovery, and soon a goodly number of land sharks, speculative pioneers, and bona fide squatters, followed to the ‘fresh fields and pastures new,’ which Con’s pluck and enterprise had opened up to them.[20]

Within a year, he had built a hut 150km up the Warragal from the Darling at what initially became known as ‘Con’s Hut’. He called the hut ‘Erins Gunyah’, and the town that grew up around it was initially called Eringonia and still later Enngonia when it was mis-spelled on the official documents. The country between there and the upper Warrego was excellent grazing country, and he established a horse station. Unfortunately for Bride, the British government was in the process of creating a new colony and the land he was claiming straddled the border which was only 35km to the north of his hut. He was never successful in acquiring a lease despite Thomas Dangar presenting ‘a petition from Cornelius Bride, complaining of having been unjustly deprived of certain lands for which he had tendered, near the Queensland border.’ [21] in 1862.

It was on the east side of the Warrego, a few miles over the border in Queensland, and Dangar sent out stock to start breeding light horses on a large scale. As the Dungars were in the front rank of importers of pure blood from the Old Country in those days, it is only natural to suppose that the stock they sent to start a venture of that kind would be of good quality. But, for some reason the horse station broke up early, and the country fell under cattle, eventually becoming part of the Tinenburra run.[22]

There are many examples of florid writing in the newspapers of the later 1800s. Few are as florid as that submitted by a writer from Walgett, published in the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser. This article begins with an account of stock movements in the district, which included ‘Dangar’s 5,600 store sheep, bound to Kindera, Darling River, and 1,500 cattle from Kirbin, Con. Bride in charge.’[23] He then goes on to tell a long story about Bride’s occupation of the Warrego, concluding with

“Con,” as he is familiarly called by the old hands in this quarter, is well qualified to pioneer a party to the ” other side of Jordan” if necessary. He once held and settled the Bunnewanah [sic] Station after three consecutive attempts by others had been defeated by the hostility of the blacks, and he is well known as the earliest settler upon the Warrego.

His name among the aboriginals of the Darling and Warrego country is a “moral caution,” and yet his policy was always tempered with mercy. Upon one occasion only was he some-what unrelenting, which was thus caused: Many years ago, when Con at first located himself at the now well-known position, which bears the name of “Con’s Hut,” upon the Warrego, he was much harassed by the blacks spearing his cattle and exhibiting very strong antipathy towards himself. They had burned his hut roof, by affixing burning embers to their spears and throwing them upon it” and laid in ambush at different times to kill him while getting a bucket of water from the creek. But upon the occasion in question, the blacks had mustered in great force a large body of cattle, and forming one vast circle by joining hands, and yelling and gesticulating they so frightened the herd that the poor brutes did nothing but rush around and round, crushing into one another until they resembled a consolidated and compact rotatory mass. By this method, suggested by the savage ferocity and wanton cruelty of the natives, were hundreds of cattle speared, some mortally, and some to escape, goaded to madness by the poisoned jag spears, but only to linger in agony for a short period. It was after discovering a raid of this kind that the unconquerable “Con” girded up his loins, and prepared his well deserved “Roland,” which is known to this day as ” Warrego law,” and hastening back to his hut to enter up judgment, he was horrified to find that his companion and hutkeeper had been mercilessly and brutally murdered in his absence. The head being scalped and the limbs dismembered, and the whole body barbarously mutilated. Con’s position was unenviable: his herd, speared and hunted, and his sole associate killed, in a hostile country, surrounded by tribes of enemies, and without the least help or aid for one hundred miles. But cool, intrepid, and undaunted, he avenged the unprovoked onslaught with terrible determination, and that very night the solitaire exacted a retribution which ever afterwards gave him undisturbed possession, and up to the present day furnishes the material for many a camp yarn.[24]

Bride’s killing of Kula and Muruwari people is told as an account of how he has laid the foundations for establishing a town where settlers can obtain their last supplies ‘before entering on the wilderness with its perils and adventures.’

David Morgan Jones was a resident of the Walgett region for some 40 years.[25] Other than in parliamentary papers, his Christian names weren’t used in any references to him in all that time. He was always known as Mr D.M. Jones. He was Thomas Dangar’s political ally, who nominated him for election to the Legislative Assembly in 1865, and best friend, who supported him ‘in his last moments’ when he died at his home, Crownthorpe, at Stanmore in 1890.[26]

Jones placed an article in five newspapers in 1869. It was an appeal for support for Bride who had fallen on hard times, and the headline was:

“CON BRIDE, THE PIONEER OF THE WARREGO. AN APPEAL”[27]

He was targeting graziers who had benefited by taking up squatting runs in country Bride had explored. Goulbourne, Maitland, Toowoomba and two Brisbane newspapers printed the appeal in which Jones summarised Bride’s life from 1857 to 1869.

After failing to secure a lease on the upper Warrego, he had returned to Bunnawanna where he continued to breed horses. He was also well known in Bourke where his horses were the most successful in weekend bush racing. Horse stealing became a major problem on the upper Darling and Bride had his arm and two ribs broken in trying to recover two of his horses in 1863[28].

Jones informed his readers that Bride

next succeeded in securing a five-mile back block at the rear of Ginge, near this township, intending to try sheep upon a small scale. After a trial of two years, however, in which he laboured hard to get water, and during which time he expended fully one thousand pounds in the attempt, he again fell back somewhat disheartened.

This was on Ualarai country, whose people he had killed at Hospital Creek.

Having still a few hundreds [sic] left he determined to embark it all in ” free selection.” This time he visited a sandhill on the back block, adjoining the Gwydir Pastoral Company’s land, and “tapped it” Having got water in twenty feet he selected a section, improved it, and, buoyed up by his extraordinary spirit, purchased a flock of some 2000, ewes. In his journey without water to his home in the desert some 500 perished ; but having landed the rest safe, he passed this loss with little regret.

A few days after this a valuable Magus entire colt, that he had just bought for £100, was smothered in the well accidentally. This only nerved him the more, and he worked and slaved with unabated strength to recover himself. His success seemed sure, and the force of his example caused the Gwydir Pastoral Company to develop their blocks by making wells.

Con had paved the way, and his well supplied them with water on the spot, while he, in the first instance, dragged his water twenty miles while putting down his own well. But the subject of our sketch was again doomed to disappointment. The heavy drought of the past two years set in; the grass was too dry to support sheep, they fell off, and at last commenced dying rapidly. At that time Con felt himself breaking down in his constitution, which, if it had been of adamant, must have given way, and during the struggle his wife and child both died, adding to the chaos of adversity.

In this strait he called in his creditors, and gave them the remnant of his worldly goods, promising to indemnify them from all loss if ever it lay in his power. But he had yet one remorseless creditor to deal with-rheumatism-which completely prostrated him, and deprived him of the use of his limbs. In this condition he sought the Hospital, from which he has now returned partially relieved, but with his means shattered, and his constitution wrecked. Poor fellow! he was once reputed to be the best hand with a horse upon the river, and the cleverest man amongst cattle; at present he is shepherding, and bush men will readily understand how acute his position is by that one word; he is but a young man, being but thirty years of age.[29]

It is rather strange that Jones was only accounting for events up to 1866. His article was dated June 1869 and doesn’t account for where Bride was between 1866 and then. Bride was back on the Warrego River.

In March 1866, both Bride and Dangar were granted leases on two properties on the Warrego. It’s highly likely that Dangar assisted Bride in securing a lease on a run called Bugga, adjoining his own lease of Grawin Addendum.[30]

Despite both runs being valued at £20, Dangar’s annual rent was set at £8.10.00 while Bride’s £10.00.00. The rent on squatters’ runs was not based on an assessment of the land’s value. Instead, it was a fixed annual fee determined by the government, and the amount varied depending on the size of the run, not its inherent value, suggesting that Bugga was substantially larger than Grawin Addendum.

By 1868, Bugga was no longer in Bride’s name and the rent had not been paid.[31] There is no evidence that Bride ever again acquired any property. All mentions in newspapers from then on were only to do with him droving stock.

In 1869, Thomas Manning the owner of the Dubbo Dispatch and Wellington Independent published an article about his visit to Brewarrina where he had met Pilliga Jemmy. He wrote:

the blacks could be found in thousands along this river not 25 years ago ; but where are they now? Can you find them in hundreds? No, nor in tens; and what, you will ask, has become of them? Some have gone back into the Mulgar [sic], and disease has done its work with them; but what has done the most deadly work has been the rifle, not in every instance in the hands of the white man, but in the hands of their own fellow countrymen.

At Brewarrina and a station close by, three blackfellow, natives of the Liverpool Plains, that had been taught the use of firearms to perfection and ditto the use of horses. These fellows, for many years shot down anything black in human shape, indiscriminately wherever they met them. one of these demons, Pelica [sic] Jemmy, told me some revolting stories. He said he had shot and poisoned 170 and Brewarrina Jemmy had killed far more than him. He related an affray that took place in a back creek, not more than 5 miles from Brewarrina, and in proof of his assertion showed me hundreds of bones (I should say the remains of forty). He, it appeared from his story, had been out on a run and had tracked a lot of cattle away from a camp. He further discovered that the cattle had been disturbed by the arrival of black to fish at the camp. He did not allow himself to be seen, but rode home, from whence an express messenger was dispatched to Merriman, and some other half-dozen other stations up the river, for all hands came down for the blackfellow hunt. All hands were ready- whites and their Namoi demons- and started at night, arriving close to the camp of the blacks before day, where they waited until daylight, then taking up positions to as to command the entire camp, they sent in a deadly volley, and before two hours there was not a black left. Some two days later, four of the same party of murderers were riding by the said spot, when they found three blackfellows that had not died, and an old gin less wounded attending to their wants. “Eloah”, said one party, “here’s a hospital”. They then got down and dispatched the whole four with a tomahawk, not caring to waste powder and shoot on them, and from that day to this, this camp is called “The Hospital.[32]

Manning also wrote of Pilliga Jemmy describing indiscriminate killings by local cattlemen, where the bodies were burned so as not to interrupt the cattle as they passed. He concluded his article with a statement that Pelica Jemmy was now also dead, having been

poisoned first, then shot, and then burned at Bunnawarra, by a man named Thompson who was committed for the deed.

Mannings reference to ‘Namoi demons’ as being part of the killing party, suggests that they were Kamilaroi men. As in the case of Pilliga Jemmy, some young indigenous men were attracted to working for the cattlemen. Perhaps the attraction of being given a horse and gun, and the fact that their own extended family group had been destroyed, meant they could avoid being killed themselves. In the following decades, the desertion rate of native police was extremely high, suggesting that they objected to killing the people of other nations.[33] As for the ‘Namoi demons’, Bride also said that there were half a dozen black boys who came with two cattlemen to assist him.

William Emanuel Kerrigan wrote a reminiscence of the 1860s, which included:

The wild blacks were that bad that all the cattlemen had to deal with them, so they rounded them up like cattle, old and young, on Quantumbone plain and shot them. There were about 400 and that is how Hospital Creek got its name. There were only two picaninnies left, a boy and a girl. The boy they took to Milroy and he was still there when I went to Milroy in 1881 and I think the girl was there too. All the cattlemen were Gilchrist and Watt, “Milroy”; Sawers and Wilson “Bundabulla”; Beaumont, “Talawanta”; McKenzie “East Bundabulla”; Mick Burrell next to McKenzie; Doyle “Corrella and “Moorabilla”; Shirt of “Langboyd”, and Crowley’s up the Barwon.[34]

Kerrigan, in naming ten cattlemen from six stations in the district, would seem to corroborate Pilliga Jemmy’s claim that a ‘half-dozen other stations up the river’ were involved.

In 1978, Dr Max Kamien, a doctor based in Bourke, published the book “The Dark People of Bourke” [35]. The title was chosen by the local indigenous people and two of the elders, Lorna Dixon and Bill Reid told him that after rainfall, they often found bones, including skulls with bullet holes in them.

Con Bride spent the rest of his life droving cattle and horses. He was most likely based at Belar near Coonabarabran, with his brother Bartholomew. It was there that he registered a horse brand in 1875. In 1877 he was responsible for droving 1,500 cattle from a run called Kirbin, near Mendoorin, 70 kilometres south of Coonabarabran to the Diamantina. In 1879, ‘130 horses, the property of T. G. Dangar, M.L.A., from Bullerawaand Tallalia stations, Namoi River, are passing for Northern Queensland in charge of Con Bride’[36]

G.M. Smith in his ‘Pioneers of the West The Massacre at Hospital Creek’[37] wrote about sharing his campfire with Bride, when Bride was returning from trying his luck on the Temora gold fields in 1883. Smith, recalled Bride saying ..

‘I suppose you know the Hospital Creek? It crosses the plains a few miles out from the Cato Creek. Strictly speaking it is not a creek — only a chain of ponds formed by the over-flow from the Narren Lake, which at high flood flows across the plains into the Bokira Greek. There were fine holes in it which held water well in dry times, and nice shady timber round them, making a good camping ground for the cattle. But it was also a good camping place for the blacks, who came there in hundreds to live on the cattle. They had been spearing the cattle some time before I was aware of the fact. When I saw cattle on the run with spears sticking in them you can guess my state of mind, and when I saw some more near the creek dead and the meat stripped off the bones, and found skeletons all round about the watering-places, I decided to act. It seemed to me that their method of spearing was to get up in the trees early in the morning with their spears and lie in wait for the cattle at the holes. The beasts that were speared very badly died close about the water, while those that were more lightly injured carried the spears for miles out on the run. Few of them ever recovered after being speared.

I tried to get the blacks to shift camp, A but they didn’t understand me, or pretended not to— which was very likely, as I could speak the native lingo pretty well. So I rode to the station as quickly as possible and brought one of my black boys to talk to them in their own lingo. When he explained what I wanted them to do they said “Baal,” which in their language means “No. They evidently didn’t want to shift, as they were doing too well where they were; but I went back home and started one of my white stockmen up to the next station with a few lines to the manager to send me all the assistance he could spare in men, arms, and ammunition. The demand was only reasonable in those days, as the white settlers had to keep plenty of arms and ammunition for self-protection and to assist each other in cases of need. Next day I was pleased to see two white stockmen and half-a-dozen black boys, all well-armed, ride up. You may be sure I lost no time in getting all my own force under arms, and we rode out to the blacks’ camp nearly twenty strong. When we got within two hundred yards of the camp I halted my small force. Then I took one of the boys and rode up to their camp. When the boy told them I wanted them to shift the old darkies got very angry, and said ‘Baal,’ as before. I took the boy back to the others, and said: ‘Now, boys, we will fire a few shots over their camp. They might take fright and clear out.’ That volley caused a great commotion in the camp. They all ran up in a bunch, like a lot of wild ducks; but there was no stampede such as we were expecting. I noticed that they were all arming with spears and womeras, and when they made a move forward I feared a rush on our small force by their hundreds: so we fired a volley into them, and a dozen or more fell. This caused a halt. Then they gathered round the wounded ones. Apparently they could not understand what had happened, and we took advantage of the confusion to send another volley whistling over their heads. That settled the matter. A general stampede took place across the plain towards the Culgoa, whence, I suppose, they had come.

When I saw them in retreat I rode away to the station, to give them a chance to attend to their wounded and retreat in order. Next day we all rode out as before to the camp, and all we could see there was a lot of empty bough gunyahs. That affair got me a bad name down below with the people who never had to deal with the natives in their wild state. Had they been in my place probably they would have spilt more blood than I did. Some went so far as to say that I should have been put on trial for what I did, but the Government was well aware of the fact that the work we were doing outback could not be done with white-gloves on, and, therefore, were not too ready to take action in such cases, but de-pended on the humanity of the white settlers to spare the natives as much as possible.

Smith finished his article by stating that Bride was in poor health when they met, and that he rode on to Quantambone station where he died in 1884. He was 50 years old and was buried in an unmarked grave among the spirits of the Baranbinja and Ualarai people he had killed.

Two years later, Quantambone was acquired by the Aborigines Protection Association and used as a Mission. The Ngemba and Murawari people were relocated there.

Occasionally between 1859 and 1929, there were articles about the indigenous people who survived the massacre or had spoken with those who had survives. One such man was ..

one-eyed Peter who died at a venerable age at Brewarrina in August, 1911. He was a noted character in the district, and spoke sorrowfully of the bad old days, when his countrymen were shot down like wild beasts. He used to explain the blacks speared cattle and sheep occasionally in return for their kangaroos, which the white man destroyed, and which represented their livestock. The whites, far from showing any regard for the lives of the original owners of the country, ignored all their rights as to property, and yet were most brutal in retaliation when their rights were transgressed.[38].

One-eyed-Peter was also known as Peter Flood. As an old man, he served several terms in jail for attacking other indigenous men with his tomahawk.[39] He and Polly Marshall, were the two children who had survived the massacre.

The final and most significant words, however, belong to an indigenous man who continued his people’s oral tradition. In 1906, when he was 9 years old, Jimmie Barker and his Murawari mother went to live with relatives on Milroy station. There he met Polly Marshall.

As a resident of the Aboriginal Mission Station at Quantambone Brewarrina, he had used an Edison phonograph to make wax-cylinder recordings of Muruwari and Ngemba elders singing. Over the years, Barker accrued 113 hours of recordings, one of the most significant examples of an ethnographic collection created within Australia.[40]

Quantambone is 15 kilometres to the east of Brewarrina on the northern bank of the Barwon River. There was a walking track along the river to Brewarrina and five kilometres from the homestead was a tree that after the massacre became known as the Butchers tree. Barker was told that

It was from the area surrounding this tree that all the trouble began. I can tell only the aboriginal version of this story. A cattle owner had lived close to where the mission was that was later established. All accounts indicate that his treatment of the natives was bad. He owned some cattle, although there were probably not as many as credited to him by the white people.

The Aborigines killed some of his cattle and this caused the trouble. Their method was to wait until the animals came close to the Butcher’s tree, where several men were concealed in the branches. Other men would gently urge the base towards the tree. Where they settled in the shade. When this happened, the men jumped from the tree and hamstrung a couple of them. The herd was then driven towards the river half a mile away, where in the twilight or moonlight more natives gathered, indulge in further slaughter or distribution of the meat. This must have happened during summer months as cattle do not seek shade in the winter and tend to scatter when driven. It was said that runners carrying be fat were set out to more distant natives, and that other Aborigines were invited to the river to share the meat. After this had happened several times, the owner of the cattle declared war on the offenders and enlisted the help of other white men. The killing of cattle at the Butchers Tree was the cause of the deaths of many Aborigines.

Only a few natives were killed at the Butchers Tree as not many were there at the time. The largest massacre was at Hospital Creek. .. Many natives were camped there and early one morning the white men rode in from 2 directions. There was a lot of shooting, and a great number of Aborigines were killed. Shooting was the main course of death, but many people also were also injured by the stirrup irons carried by the white men. The firearms used at that time were muzzle loaders shooting lead balls. Groups of Aborigines either lived or met near the water, and it is thought that a number of those killed at Hospital Creek may have had nothing to do with the slaughter of cattle at the Butchers Tree. It is said that some men. Escaped being killed near the tree and ran to join the group at Hospital Creek. The country is open there and it was difficult for the Aborigines to hide or escape. Very few survived. Skeletons and bones can still be seen there today, although I saw many more in 1928. The bone bones must have been there for a long time and their quality indicated that a large number of natives had been left dead or dying. The massacre occurred at a time when there was a movement amongst the whites to kill all Aborigines when found in a group or even separately.[41]

If a colonial frontier massacre is defined as the deliberate killing of six or more relatively undefended people in one operation[42], then the killings at Hospital Creek, at the river, waterholes and surrounding country in 1859 meet that criteria. The stories I have quoted and referenced are not “bush yarns “or “campfire yarns”, they are written and oral records of events that took place on Ngemba, Murrawarri, Euahlayi, Weilwan, Ualari, Barranbinya and Kamilaroi country. The bones of 40 people witnessed by Manning in 1869, and the many intermingled skeletons described by Barker, were not on “traditional burial grounds”, as claimed by some historians.

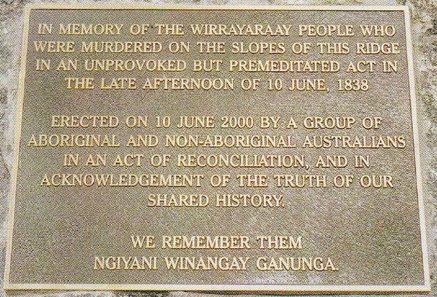

We will never know if there was just the one massacre at Hospital Creek or many massacres over several years, however there is no doubt that many hundreds were killed, and thousands vanished from country in just 25 years. These oral histories, contemporary writings, and physical evidence collectively affirm that the Hospital Creek massacre in 1859 was an extensive event. They challenge historical denial and underscore the need to acknowledge and confront Australia’s violent frontier past. Recognizing such trauma is needed for reconciliation, respect for, and the honouring of, the enduring cultural memory of Indigenous communities.

[1] Kelly, Lynne. The Memory Code: The Traditional Aboriginal Memory Technique That Unlocks the Secrets of Stonehenge, Easter Island and Ancient Monuments the World Over. Allen & Unwin, 2016

[2] “Narran Wetlands”. Important Bird Areas factsheet. BirdLife International. 2011.

[3] Sturt, Capt. C. 1833. Two expeditions into the interior of Southern Australia during the years 1828, 1829, 1830, and 1831…etc, (2 vols). Smith, Elder and Co., London. (1965 facsimile edition, Public Library of South Australia).

[4] https://www.ruralaid.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Brewarrina_CDP.pdf

[5] Mitchell TL (1839) ‘Three expeditions in the Interior of Eastern Australia, with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix and of the present colony of New South Wales, Vol. I.’ (T. & W. Boone: London, UK)

[6] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 30 September 1843, page 1

[7] Hawkesbury Courier and Agricultural and General Advertiser 27 February 1845, page 3

[8] https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/timeline.php

[9] https://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/dangar-thomas-gordon-tom-3361

[10] https://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/dangar-thomas-gordon-tom-3361

[11] https://www.walgett.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/v/1/department/planning/documents/thematic-history-walgett-shire.pdf

[12] Bathurst Free Press and Mining 25 April 1896, page 2

[13]

Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal (NSW : 1851 – 1862; 1872; 1882; 1885 – 1897; 1899 – 1904), Saturday 25 April 1896, page 2

[14] Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer 19 June 1858, page 2

[15] Sydney Mail Wednesday 12 September 1928, page 53

[16]Mount Alexander Mail 11 May 1860, page 7

[17] https://nahc.ca.gov/cp/timelines/northeast/

[18] Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 19 October 1895, page 804

[19] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 8 June 1869, page 4

[20] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser Tuesday 8 June 1869, page 4

[21] The Newcastle Chronicle and Hunter River District News 5 Jul 1862 Page4

[22] Sydney Mail 8 January 1930, page 37

[23] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 24 May 1877, page 2

[24] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 24 May 1877, page 2

[25] https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/historictabledpapers/files/140689/LCTP%201898%20433-495_007.pdf

[26] https://oa.anu.edu.au/obituary/dangar-thomas-gordon-tom-3361

[27] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 8 June 1869, page 4

[28] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 5 March 1863, page 3

[29] Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser 8 June 1869, page 4

[30] New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, 23 March 1866 (No.59), page 766

[31] New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, 13 March 1868 (No.61), page 719

[32] Empire (Sydney, 26 March 1869, page 3

[33] Richards, Jonathan (2008). The Secret War. St Lucia: UQP. ISBN 9780702236396.

[34] Dargin 1976 quoted in Rando, 2007, p38

[35] The dark people of Bourke : a study of planned social change / Max Kamien. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies ISBN: 9780855750749

[36] Wagga Wagga Express 21 June 1879, page 5

[37] Sydney Mail 12 September 1928, page 53

[38] Northern Star 28 July 1914, page 8

[39] Warwick Examiner and Times 20 September 1911, page 5

[40] The voices of Jimmie Barker: historic trove preserved https://centralnews.com.au/2023/10/05/the-voices-of-jimmie-barker-historic-recordings-preserved/

[41] https://archive.org/details/twoworldsofjimmi0000bark/page/124/mode/2up

[42] https://humanities.org.au/power-of-the-humanities/the-australian-wars-new-insights-from-a-digital-map/